China’s Evolving North Korea Policy

Heungkyu Kim

The Center would like to acknowledge that this publication was generously supported by the Korea Foundation.

Introduction*

It would seem common sense that China’s policies seldom change due to its complexity, rigidity, and size of decision-making system. Therefore, policies should be characterized more by continuity than change. China’s North Korea policy has been a typical example of such a perception and bias. Conventional wisdom is that North Korea has been China’s strategic asset and natural ally due to its ideology, socialist system, geographical proximity, and the fact that they fought on the same side in the Korean War. However, carefully examining China’s policies on North Korea, evolutions in its policies can be discerned depending on changing perceptions of national identity and strategic orientation.

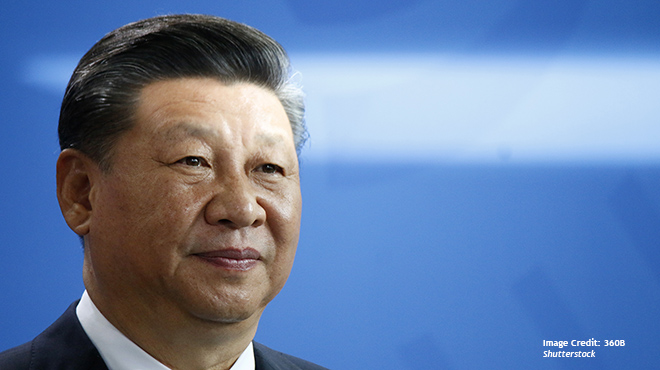

Deciphering China’s North Korea policies has recently been a subject of intense debate in South Korea as well as in other countries. Under Xi Jinping, China’s policies towards North Korea have fluctuated at the same time as China has come to increasingly identify itself as a great power. Accordingly, China views the two Koreas through the prism of great power politics combined with more pragmatic approaches. As the U.S.-China strategic competition intensifies, it has become the most important variable in China’s foreign policies.

This paper proceeds by first outlining the different characterizations of China-North Korea relations. It then considers the different policy orientations of China’s strategic schools based on their perception of China’s status in the world and how these have influenced perceptions of North Korea. Finally, changes, drivers, and implications of China’s North Korea policy under Xi Jinping are examined.

* This essay is in large part based on and revised from the author’s previous academic research and policy papers. In particular, see Kim Heung-kyu, “From a Buffer Zone to a Strategic Burden: Evolving Sino-North Korea Relations during Hu Jintao Era,” The Korean Journal of Defense Analysis 22(1) 2010; also see Kim Heung-kyu, “U.S.-China-South Korea Coordination on North Korea,” CFR Online Journal, November 2017.

Characterizing China-DPRK Relations

Broadly speaking, four different characterizations of China-North Korea relations have existed in Chinese strategic thinking over time.

The first conforms to conventional wisdom of China and North Korea as allies. They fought shoulder to shoulder in the Korean war against the United States. The Sino-North Korean Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Mutual Assistance, signed in 1961, possesses a military intervention clause to defend each other if a third party intervenes militarily. In this relationship, they are described as blood-shared allies. However, this view of relations has diminished since China adopted the reform and opening policies in 1978 and established a formal relationship with South Korea in 1992.

The second categorization is one of traditional good neighborly and friendly relations, which has been the formal description of relations by Chinese authorities since the mid-1990s. Some experts argue that this relationship is on a par with that of allies due to the concept of “traditional,” signifying special. However, the term is common in China’s diplomatic usage in describing the relationship with former socialist countries such as Albania, as well as present-day Vietnam and Cuba. Accordingly, North Korea falls under the same category as these countries. In fact, the most special relationship described by China is the “all-weather” relationship bestowed to Pakistan, and perhaps the new era of comprehensive active strategic cooperative partnership with Russia.

The third description is that of strategic partnership. Under the harsh security environment of the Cold War, China and North Korea maintained friendly and cooperative relations through their respective strategic calculations despite their level of trust being low and lack of special liaison between them. Thus, the strategic competition between the U.S. and China and continuing Cold War-like security environment in Northeast Asia explains the seemingly special bond between China and North Korea.

Fourth is normal state-to-state relations. The key concept in this description is that of national interest. In particular, China as a rising great power did not want to maintain special relations with “rogue” states like North Korea, which it perceived as damaging its reputation and running counter to its own national interests. Former President Hu Jintao revealed his determination to establish normal state-to-state relations in front of North Korean military leader Cho Myeong-rok, who visited Beijing in 2003 after reviewing China-North Korea relations. While Cho emphasized traditional blood-shared relations, Hu promptly corrected him.

China’s North Korea policies have thus fluctuated based on these four different types of relationships over time. No single view has necessarily been dominant in the policies. Notwithstanding, from Hu Jintao onwards, China’s North Korea policy has arguably become the most controversial issue in Chinese foreign policy.

Changing Chinese Strategic Thinking and Influence on North Korea Policies

Reflecting its changing power and influence, strategic ideas in China have also evolved and diversified. Revolutionary foreign policies were dominant for roughly three decades of the Mao Zedong period. This was followed by the opening up and reform policies during the next three decades under Deng, Zhang, and Hu. Identifying China as a great power, Xi commenced the era of great power foreign policy: China was no longer merely a continental or regional power, but a global power.

Chinese strategic thinking on the Korean Peninsula has accordingly changed and is no longer monolithic. The traditional image of a top-down approach to Chinese decision-making has also caused a misunderstanding of Chinese foreign policy. As of the end of 2019, four groups of Chinese thinkers can be identified depending on their perceptions of China’s status in the world. I categorize these four schools respectively into the “traditional geopolitics school” which includes chauvinistic nationalists, the “developing country school,” the “newly rising great power school,” and the “great power school.”

The “traditional geopolitics school” regards North Korea as a buffer zone and a strategic asset to counter the U.S.-led bilateral alliance mechanism in Northeast Asia. Traditionalist hawks argue that China must consider North Korea as one of its key allies to mitigate U.S. hegemony; hence, China should take measures to strengthen its “special ties” with the reclusive regime. Accordingly, this group regards South Korea as a hostile state allied with the U.S. to counter China. This school constituted the mainstream view before Hu Jintao. During Hu’s era, the majority of Korea experts and old military elites belonged to this school.

The “developing country school” holds that despite some differences between China and the U.S., pursuing sound relations with the U.S. should be favored. This constituted a major line of Chinese foreign policy during the Jiang Zemin and into the Hu Jintao era. Taking a pragmatic approach according to the principle of “hiding capacities and biding time,” they support affirming China’s foreign policy goal of establishing peaceful relations with neighboring states including South Korea as well as great powers for the purpose of China’s continued economic development until at least 2020, when a “medium-level of well-off society” (小康社會 / xiaokang shehui) would be reached. On this basis, they sought to transform the relationship with North Korea into a normal state-to-state relationship. During the Hu era, the majority of think-tank experts in Beijing belonged to this group.

The “newly rising great power school” regards China as a rising great power, second only to the United States. As such, it is surmised that Chinese interests may collide head-on with those of the U.S. The ideas of this group gradually gained traction among the Chinese populace and elites around the time of the 17th Party Congress in 2007, even before the financial crisis. They are likely to favor playing a more active role as a great power in the region in dealing with arising issues, as well as in preserving China’s interests on the Korean Peninsula. They are likely to oppose unilateral intervention in North Korea either by the U.S. or South Korea. This group of thinkers became the mainstream in Xi Jinping’s foreign policy circle.

The “great power school” became salient and strong supporter for Xi Jinping’s audacious global foreign policies, evolving from the traditionalist and newly rising great power schools. They believe that China will become a world leader sooner or later and thus accomplish the task of China’s dream which Xi Jinping depicted at the 19th Party Congress in 2017. Accordingly, competition with the U.S. is viewed as inevitable which it will ultimately overwhelm. In this respect, the Korean Peninsula is seen as a locus of strategic competition with the U.S. and thus an area of competing influence. South Korea turns into a lynchpin for China’s strategic interests. North Korea remains a strategic asset although its abrupt behavior must be managed according to China’s interests.

The evolving strategic thinking of China will certainly continue to influence its North Korea policy as well as future relations between China and South Korea.

North Korea Policy Under Xi Jinping

Xi Jinping’s early leadership witnessed a change in Chinese mainstream strategic thinking from the “developing country” school to the “newly rising great power” school. The former, identifying China as a developing country, viewed stabilization of the Korean Peninsula as critical to China’s economic development. However, the latter school of thought pays relatively more attention to the strategic interests and role of China as a great power.

Accordingly, policy after North Korea’s third nuclear test in 2013 was still in between maintaining the status quo and imposing limited sanctions, reflecting Hu’s legacy. However, after the fourth nuclear test in January 2016, policy under Xi moved increasingly towards imposing sanctions. As a great power, China appeared to send a strong signal to Pyongyang that it would no longer allow North Korea’s behavior to hijack China’s foreign policy.

Table 2 (in the pdf version) captures how proponents of limited and more stringent sanctions on North Korea have come to represent the majority opinion among China’s schools of thought on North Korea. Noteworthy too is how those supporting abandonment of North Korea have also increased; under Hu, almost no one supported this view publicly.

Such policy changes appear to reflect changing tides in academia and among experts, possessing their own regional, academic, functional, and generational foundations. They compete against each other to secure policy access and expand influence.

Thus, China under Xi Jinping is not shy of wielding its power bluntly if it feels its national interests to be damaged or threatened. This was further evidenced by China’s strong reaction to North Korea’s consecutive nuclear tests in 2016-17 as well as South Korea’s introduction of the THAAD anti-missile system in 2017, to which China responded through trade retaliation.

At the same time, it is obvious that Beijing has become more active regarding the North Korea nuclear issue and proposed in 2016 a new dual track mechanism to stimulate parallel dialogues to pursue a peace treaty and denuclearization simultaneously. This dual-track mechanism is China’s primary strategy in dealing with the North Korea nuclear issue for the foreseeable future.

On the one hand, China hopes to use North Korea issues, namely denuclearization, as a means for cooperation between the U.S. and China, whose scope for cooperation has increasingly shrunk. China is afraid moreover that North Korea’s provocations threaten China’s strategic interests and that it could become entrapped as in the Korean War. On the other hand, China is also afraid of the growing influence of South Korea, and eventually the U.S., over North Korea.

Beijing has reinterpreted its strategy for the Korean Peninsula more ambitiously than before. Beijing has sought to extend its influence over the whole Korean Peninsula instead of just protecting its buffer zone. The adjustment of Korea policies has brought tremendous challenges to China of how to maintain balance and fairness between the two Koreas, while protecting China’s strategic interests.

An Era of Ongoing Strategic Competition

Given the past track record and potential for changes in China’s North Korea policy, it is essential to note that China’s strategic milieu has not changed. Accordingly, it should not be assumed, as many South Koreans have done, that China will increasingly view North Korea as a “strategic burden.”

The U.S.-China strategic rivalry is ongoing; the South Korea-U.S. alliance and the U.S. military presence on the Korean Peninsula continues; the level of distrust between South Korea and China is still high; the potential of a trilateral security alliance among South Korea, U.S., and Japan against China exists; and the Taiwan Strait issue has not been resolved.

In the middle of intensifying U.S.-China competition, furthermore, China has even found renewed strategic value in North Korea. China has therefore sought to some extent to recover its relationship with North Korea. In Beijing’s reasoning, China needs to have a better relationship with North Korea to manage its disruptive behavior and prevent North Korea from being a variable in U.S.-China relations.

Furthermore, Chairman Kim Jong Un quickly recognized China’s apprehension of being side-lined in U.S.-DPRK talks in 2017-18, consequently visiting China four times. Kim seemed to assure Xi that North Korea would not damage China’s strategic interests in the U.S.-North Korea negotiations in exchange for reassurances of the safety of Kim’s regime.

In sum, China is unwilling to abandon North Korea as a strategic ally. Should the strategic competition with the United States intensify, China might tighten its strategic interests with North Korea even further.

Dim Prospects for Denuclearization

So far, China’s new Korea polices can be evaluated as only partially successful. The dual track approach that China has proposed has been broadly accepted as a guiding principle to North Korea denuclearization negotiations. In spite of Trump’s accusations of China as a spoiler, Beijing has stuck firmly to the principle of denuclearization and has upheld the UN sanctions regime, working as a stabilizer on the Korean Peninsula.

However, the prospects for denuclearization on the Korean Peninsula are not necessarily optimistic. Where the focus is more on strategic competition, neither the U.S. or China have placed denuclearization on the Korean Peninsula as a policy priority.

Furthermore, despite the recent thawing of relations and intensified cooperation between China and North Korea, there remains a deficit of trust in bilateral relations. By affirming self-reliance policies in the recently held Central Party plenum in December 2019, North Korea seeks to minimize the negative influence of the U.S.-China strategic competition while strengthening its own nuclear capability. Should North Korea return to its brinkmanship approach, however, Beijing will be forced to reexamine its current North Korea policy in line with its new identity as a great power.

The Moon Jae-in government, for its part, has not yet given up on talks with North Korea and resolving the denuclearization issue through dialogue. If these efforts should fail, however, South Korea will find itself at the crossroads between self-armament and further strengthening its alliance with the U.S.

Conclusion

The prevailing wisdom has been that China was not likely to take any initiative on Korean Peninsula issues; instead it would seek to maintain the status quo. However, with the rise of China and the escalation of the nuclear crisis, China’s North Korea policy has evolved from that of traditional allies to a normal state-to-state relationship, to a combination of the two.

Under Xi Jinping, China’s relationship with North Korea has dramatically fluctuated between high tides and low ebbs. North Korea’s consecutive nuclear and missile tests led to the widely observed deterioration in China-DPRK relations in which Beijing voted in the UN Security Council for unprecedently harsh sanctions on North Korea. Since 2018, however, relations have improved as Beijing seeks to provide modest diplomatic and economic support to North Korea while advocating a dual-track peace and denuclearization process.

The key factor in explaining both this relationship and China’s policy change is that of pursuing its own national interests, thus expanding its influence over and limiting U.S. influence on the Korean Peninsula. In the near future, China will pay close attention to the evolving regional security dynamics, in particular U.S. policies and the balance of power between Beijing and Washington. While neither the U.S. nor China are likely to back down on the Korean Peninsula, nor do they seek open confrontation.

Looking ahead, the U.S.-China strategic competition and how it unfolds is and will be the most important intervening variable in China-North Korea relations. South Korea’s positioning in regard to the strategic competition between the U.S. and China will also very likely influence the evolution of China’s North Korea policies.

Author Bio

Dr. Kim Heung-kyu is founder and director of the China Policy Institute at Ajou University in South Korea. He currently also serves as a foreign policy advisor on several committees to the South Korean president and government. He obtained his PhD in political science from the University of Michigan. He was a Visiting Fellow at ISDP in February 2020.

ISDP

The Institute for Security and Development Policy is an independent, non-partisan research and policy organization based in Stockholm dedicated to expanding understanding of international affairs. With its extensive contact network with partner institutes in Asia, each year ISDP invites a number of visiting researchers as well as guest authors from the region to participate in research, discussion, and exchange with European scholars and policy officials. ISDP’s Focus Asia series serves as a forum for these researchers as well as guest authors to provide and clarify their viewpoints on the contemporary issues and challenges concerning their countries, adding a much-needed Asian perspective to the policy and research debate.

For enquiries, please contact: info@isdp.eu

No parts of this paper may be reproduced without ISDP’s permission.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this paper are those of the author only and do not necessarily reflect those of ISDP or its sponsors.