China’s Great Retreat: Unpacking the Boom, Bust, and Strategic Withdrawal from Africa

Brian Iselin

China’s presence in Africa, once seen as a juggernaut of foreign investment and aid, is now experiencing an unmistakable and sharp decline. For the better part of two decades, China has projected itself as a benevolent partner to the continent, with grand ambitions rooted in geopolitical strategy, resource extraction, and an expanding global footprint. From infrastructure development to large-scale loans, China’s influence peaked in 2018. However, what we are witnessing now is a remarkable contraction—one that mirrors China’s own domestic struggles. The collapse of Chinese aid and FDI in Africa over the past decade isn’t just an economic story; it’s a microcosm of broader, fundamental issues rooted deep within China’s own economy.

So, what’s happening here? And, more importantly, what can we learn from it?

The Nature of China’s Engagement with Africa

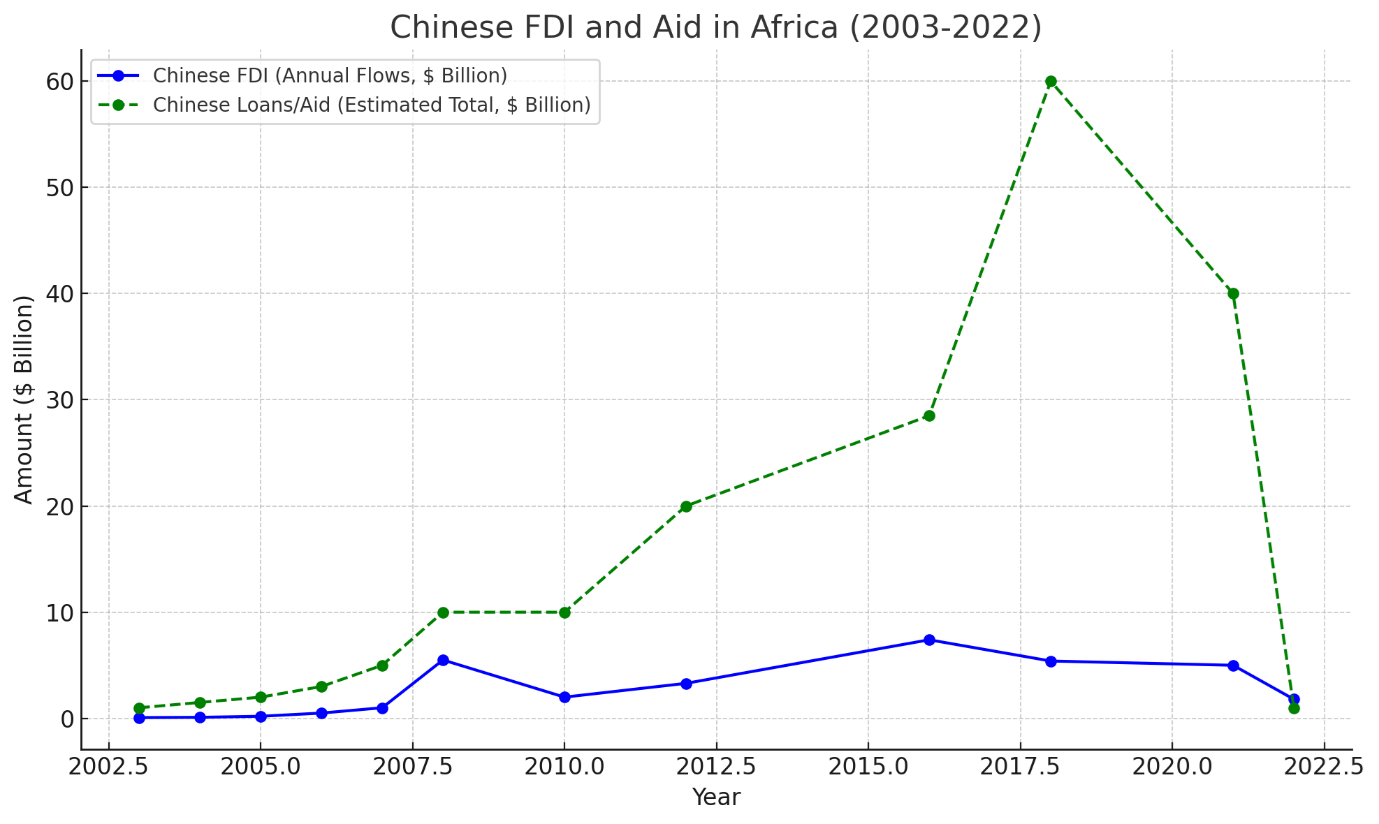

Let’s start by examining the nature of China’s African strategy. Beginning in the early 2000s, China, like a titan awakening, shifted its focus outward—reaching beyond its borders for influence, resources, and strategic partners. Africa became a crucial region in China’s geopolitical chessboard, providing natural resources, access to growing markets, and a stage for expanding the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Between 2000 and 2018, Chinese investment in Africa skyrocketed, driven by Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) in critical sectors such as infrastructure, energy, mining, and manufacturing. Alongside FDI came development aid, often in the form of concessional loans, which supported the construction of roads, bridges, and power plants across the continent.

China’s engagement was hailed as a win-win—a strategy rooted in the doctrine of South-South cooperation, which promoted development through shared interests rather than paternalistic models of aid common in Western countries. Unlike traditional Western aid, China’s aid was tied to economic projects, usually large-scale infrastructure initiatives, that not only benefitted recipient countries but also provided a return on investment for China. Many African leaders lauded this approach, viewing China as an alternative to the cumbersome and condition-laden aid coming from the West.

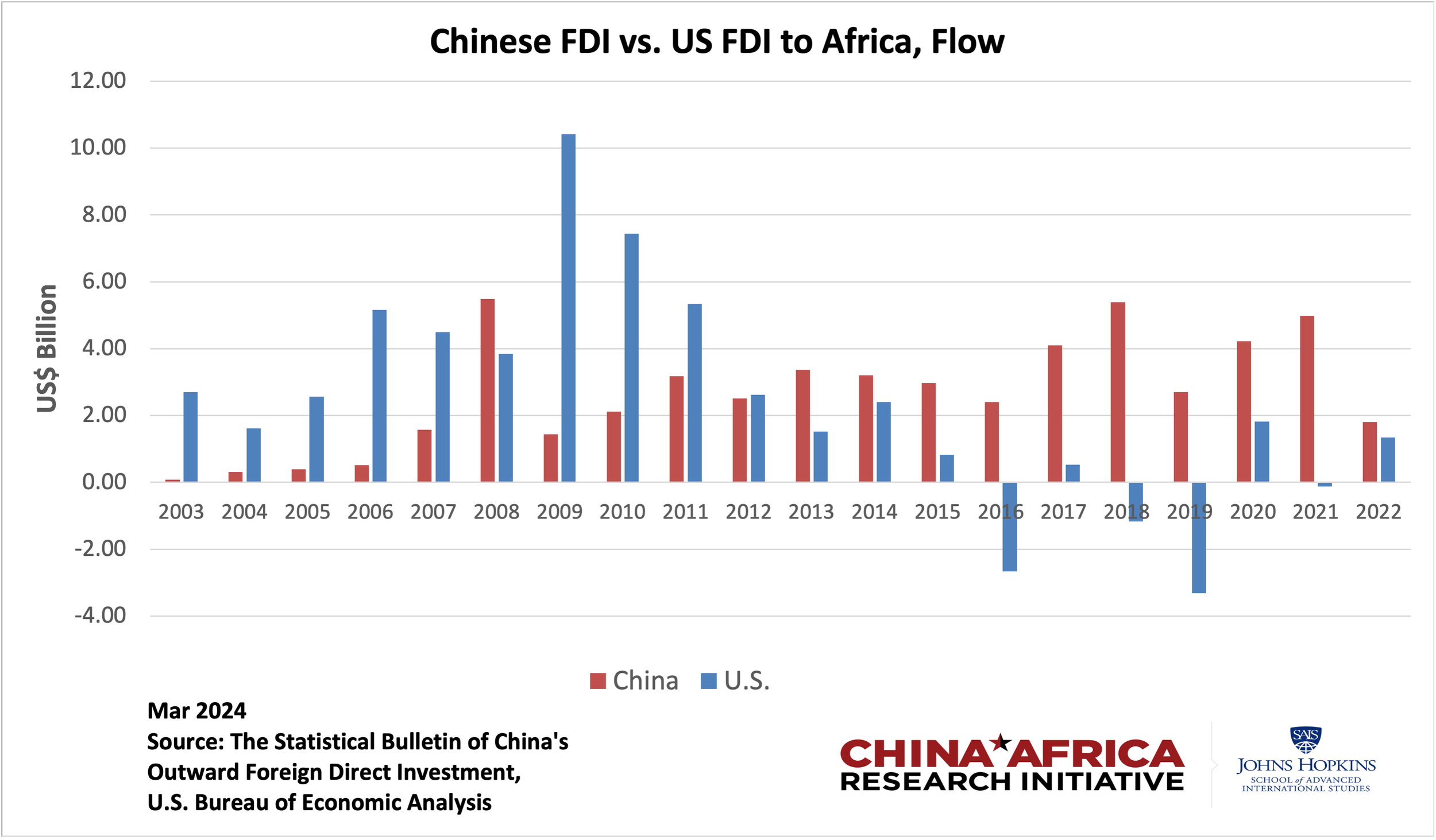

Figure 1: Chinese FDI in Africa 2003-2022. Source: The Statistical Bulletin of China’s Outward Foreign Direct Investment, U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, China Africa Research Initiative at Johns Hopkins University, March 2024

Between 2000 and 2020, China funnelled over $170 billion in development finance to African countries, largely through its development banks—the China Development Bank (CDB) and the Export-Import Bank of China (CHEXIM). This was a time of unprecedented growth, not only for Africa but also for China, whose GDP was rising, and whose global stature was solidifying. It was a mutually beneficial arrangement—at least on the surface.

The Peak: 2018 and the Apparent Success of China’s African Strategy

By 2018, China’s engagement with Africa had reached its zenith. Annual inflows of Chinese FDI into Africa hit $5.4 billion. Major infrastructure projects, from railways in Kenya to power plants in Ethiopia, were underway, creating visible signs of development across the continent. China’s Belt and Road Initiative had made inroads into Africa, positioning China as the primary builder of the continent’s infrastructure.

Aid also reached its peak during this period. In 2016, as the BRI expanded, Chinese aid to Africa surged, marking the high point of Chinese concessional loans, project financing, and other forms of support. The narrative at the time was clear: China was here to stay, and Africa was the arena where China would solidify its geopolitical might for decades to come.

Yet beneath the glittering surface, cracks were beginning to show.

The Decline: 2018-2022

After 2018, the tide began to turn. What had seemed like a relentless wave of Chinese investment and aid started to recede, and with alarming speed. Between 2018 and 2022, Chinese FDI to Africa plummeted by 66.7%, dropping from $5.4 billion to a mere $1.8 billion. Aid, too, took a nosedive after 2016, with fewer new projects being launched, and many existing commitments either scaled back or left unfulfilled.

This sharp decline in FDI and aid is not incidental, nor is it a reflection of Africa’s changing needs. Rather, the source of this drawdown lies squarely in the economic realities that China itself has been grappling with. China, for all its economic might, has been facing severe structural challenges at home. And these challenges have forced it to pull back from its grand ambitions abroad, Africa included.

Why Has China Withdrawn?

To understand China’s retreat from Africa, we must first look at what’s happening within China itself. The answer, quite simply, is that China’s economy has been in trouble. The economic slowdown that began in earnest around 2016 has intensified, and the repercussions are now being felt worldwide. Let’s unpack this further.

- China’s Economic Slowdown

The Chinese economy, which once boasted double-digit growth, is no longer the unstoppable force it once was. GDP growth has slowed significantly, dropping to around 6% in 2019 and falling further since the COVID-19 pandemic. But this isn’t just a temporary blip; it’s the manifestation of deeper problems. China’s manufacturing sector is struggling, its export-driven model is under strain, and its domestic consumption remains weak. Meanwhile, a looming property market crisis—exemplified by the collapse of giant developers like Evergrande—has sent shockwaves through the economy. The end result? China has less money to throw around.

When your own house is on fire, you naturally turn inward. China’s focus has shifted to fixing its own economic problems, with less bandwidth available for ambitious, capital-intensive projects abroad. Infrastructure investment, particularly in Africa, is expensive, and Chinese policymakers have rightly recognised that continuing to funnel billions into foreign projects, while their own economy is suffering, is simply unsustainable (1).

- Debt Overhang and Risk Aversion

A second major factor contributing to China’s pullback from Africa is the growing concern over debt. Several African countries, including Zambia, Ethiopia, and Kenya, have been accumulating massive debt as a result of Chinese loans. Zambia, for example, defaulted on its sovereign debt in 2020, becoming the first African nation to do so during the COVID-19 pandemic. These countries, heavily reliant on Chinese financing, have found themselves in precarious positions, struggling to meet their debt obligations.

China, facing these realities, has become far more cautious about extending new loans to heavily indebted countries. The risks are now too high, and Chinese investors are understandably wary of committing more capital to regions where debt renegotiation is becoming the norm (2). As a result, many projects that were once funded by Chinese banks have been scaled back, and new investments have slowed to a trickle.

- Geopolitical and Geoeconomic Shifts

The geopolitical landscape has also shifted in recent years, with increasing competition between China and Western powers in Africa. The United States, the European Union, and other countries have responded to China’s growing influence by stepping up their own engagement in the continent. The EU’s Global Gateway initiative, for instance, aims to rival China’s Belt and Road Initiative by offering alternative financing models that are less tied to resource extraction and debt.

This competition has created a more complex environment for Chinese investments. While China remains a significant player, it is no longer the dominant force in African development. Western countries, offering alternative financing, have made it more difficult for China to maintain its earlier levels of influence (3). In response, China has become more selective in its investments, prioritising projects that align with its long-term strategic goals and avoiding those that pose significant financial or geopolitical risks.

- Shifting Priorities in Aid Strategy

Beyond FDI, China’s aid strategy has also evolved. Since 2016, Chinese aid has shifted away from large-scale infrastructure loans toward more targeted forms of support, including debt restructuring and capacity-building initiatives. This reflects a growing recognition within China that many of its earlier investments in Africa were not yielding the expected returns, both financially and in terms of geopolitical influence.

While China remains an important development partner for many African countries, it is clear that the era of large, resource-backed infrastructure loans is coming to an end (4). Instead, China is focusing on smaller, more manageable projects that provide a clearer return on investment, both economically and diplomatically.

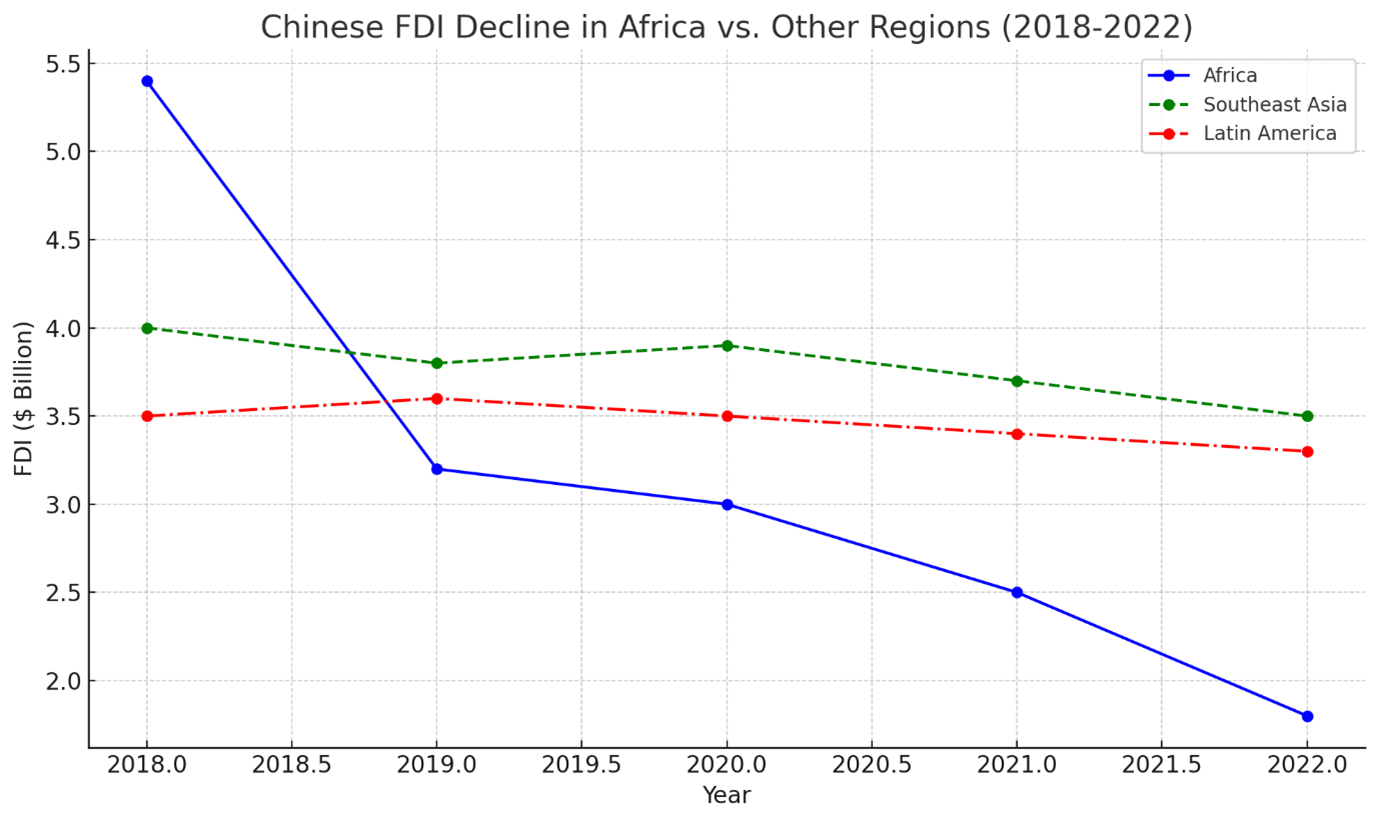

Comparative Context: Africa’s Steeper Decline in Chinese FDI

Since 2018, Chinese FDI has been in decline globally due to China’s domestic economic challenges, but this decline has not been uniform across all regions. In Africa, the drop in Chinese FDI has been more pronounced compared to other regions such as Southeast Asia and Latin America.

As shown in the chart, Africa’s FDI inflows from China plummeted from $5.4 billion in 2018 to $1.8 billion in 2022. This represents a significant 66.7% reduction over the period. In contrast, Southeast Asia and Latin America experienced much smaller declines in Chinese FDI. In Southeast Asia, FDI inflows dropped from $4.0 billion in 2018 to $3.5 billion in 2022, and in Latin America, the FDI inflows saw only a slight reduction from $3.5 billion to $3.3 billion.

Why Is Africa’s Decline Steeper?

Several factors explain why Africa has experienced a more severe contraction:

- Debt Sustainability: Several African countries, such as Zambia and Kenya, have faced severe debt challenges. This has made Chinese lenders more cautious about extending further loans or making new investments in these countries. As a result, FDI linked to large infrastructure projects has slowed.

- Infrastructure Overdependence: Unlike other regions where Chinese investments have diversified into technology and renewable energy, Africa’s FDI from China remains heavily concentrated in resource extraction and large-scale infrastructure projects, which have been affected by tighter capital controls and debt renegotiation.

- Geopolitical Competition: In Africa, China faces increasing competition from Western nations offering alternative financing models that are not tied to resource extraction or heavy debt obligations. In contrast, Southeast Asia and Latin America have seen more stable Chinese investments due to their stronger economic linkages and diversified industries.

This comparative analysis illustrates that Africa has been hit the hardest by China’s pullback in global investment, driven largely by the unique economic vulnerabilities and structural reliance on Chinese loans and infrastructure funding.

The chart visually underscores this disparity, showing Africa’s steeper FDI decline compared to other regions.

The Consequences for Africa

The decline of Chinese FDI and aid is a double-edged sword for Africa. On one hand, the reduction in Chinese investment has created fiscal challenges for many African governments that relied heavily on Chinese loans to finance their infrastructure projects. Countries like Kenya and Zambia have struggled to complete large-scale infrastructure initiatives, and the lack of Chinese financing has left many projects unfinished or stalled.

On the other hand, China’s retreat has forced some African nations to diversify their sources of finance. Many governments have turned to other global powers, such as the United States, the European Union, and India, to fill the gap left by China. This has led to a more competitive environment for foreign investment in Africa, potentially giving African countries more leverage to negotiate better terms (5).

Additionally, China’s withdrawal has prompted some African nations to focus more on domestic resource mobilisation and public-private partnerships as alternative means of financing development. Ethiopia and Rwanda, for example, have increasingly turned to domestic capital markets and international bond issuances to fund their infrastructure projects, reducing their reliance on Chinese loans (6).

The Belt and Road Initiative

The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has been a significant part of China’s engagement in Africa. The BRI, launched by China in 2013, seeks to enhance global trade routes and infrastructure, and Africa is an important region within this strategy. Several African countries have signed agreements to participate in the BRI, including major economies like Egypt, Kenya, South Africa, Ethiopia, and Nigeria, as well as other nations across the continent such as Tanzania, Djibouti, and Angola. These countries have benefitted from Chinese investment in critical infrastructure projects like railways, ports, roads, and energy plants, which are part of the broader BRI network.

The BRI and African Nations

Africa’s strategic location makes it a key part of the BRI, particularly for maritime routes. For example:

- Kenya has been a focal point of the BRI, with the construction of the Mombasa-Nairobi Standard Gauge Railway, a flagship BRI project.

- Egypt is another strategic partner in the BRI, especially with the development of the Suez Canal Economic Zone, crucial for connecting trade routes between Europe and Asia.

- Djibouti hosts China’s first overseas military base, emphasising its importance within the BRI framework.

Impact of the Drawdown on BRI Projects

However, the recent drawdown in Chinese FDI and aid has also impacted BRI projects in Africa, though not uniformly. While China remains committed to the BRI, the financial constraints faced by China’s economy have led to a slowdown in new project announcements and funding. The economic challenges at home have forced China to become more selective with its investments, focusing on projects that offer strategic long-term returns rather than large-scale infrastructure projects that are riskier or yield slower financial benefits.

In countries like Kenya and Ethiopia, where debt levels have surged due to Chinese loans for BRI-related projects, there has been a noticeable slowdown in further investments. Some of the ambitious projects have stalled or faced delays, and new BRI deals are being carefully scrutinised. Meanwhile, China has shifted its focus to restructuring existing debts rather than extending new loans, which has limited the expansion of BRI-related infrastructure.

That said, not all BRI investments have faced the same level of decline. Strategic projects that directly tie into China’s long-term geopolitical goals, such as access to critical natural resources or key maritime routes, are still receiving attention. In contrast, other projects have experienced significant reductions in financial commitment.

Where is the BRI’s Future in Africa?

While the BRI remains a cornerstone of China’s foreign policy, its scale and scope in Africa have been affected by the broader economic realities facing China. The drawdown in FDI and aid has inevitably spilled over into BRI projects, although some of the most geopolitically critical projects may still proceed. African countries within the BRI framework will need to navigate this evolving landscape, exploring new ways to finance their infrastructure needs while balancing the shifting priorities of their largest financial partner.

This selective approach to BRI investments may lead to more targeted, smaller-scale projects in sectors such as digital infrastructure and renewable energy, as China looks to secure both economic and strategic benefits while minimising financial risks.

China’s Future in Africa

So, what does the future hold for China in Africa? Despite the recent drawdown in FDI and aid, China’s influence in Africa is far from diminished. In fact, China’s long-term strategic interests in Africa remain strong, particularly in key sectors such as resource extraction, infrastructure, and digital technology.

However, the nature of China’s engagement is likely to evolve. Going forward, we can expect to see more targeted investments, focusing on sectors that offer both economic returns and strategic geopolitical value. For example, renewable energy, digital infrastructure, and technology transfer are emerging as key sectors that align with China’s broader global ambitions, particularly in the context of the green economy and digital connectivity (7).

In addition to its economic engagement, China’s military and security presence in Africa is growing. China’s base in Djibouti, established in 2017, represents its first overseas military installation, and there is ongoing speculation about the establishment of additional bases in West Africa and other strategic regions (8). This growing military footprint signals that while China’s economic investments in Africa may be slowing, its strategic interests—particularly in maintaining influence in key geopolitical locations—remain strong.

China will also continue its diplomatic engagement through forums like the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) and initiatives like the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). These platforms provide China with opportunities to maintain its soft power influence, even as its financial involvement wanes. Cultural exchanges, educational programs, and media influence will likely become more prominent tools in China’s diplomatic arsenal as it seeks to maintain its presence in Africa (9).

Conclusion: The Lesson of Overreach

China’s experience in Africa over the past two decades is a cautionary tale of ambition, expansion, and eventual recalibration. At its peak, China’s economic engagement in Africa seemed unstoppable, with billions of dollars in FDI and aid transforming the continent’s infrastructure and development landscape. However, as we have seen, the domestic realities of China’s economy—marked by slowing growth, rising debt, and structural imbalances—have forced it to scale back its ambitions abroad.

This retreat serves as a reminder that even the most powerful nations are not immune to the constraints of economic reality. China’s withdrawal from Africa is not just about its African strategy; it’s a reflection of the broader challenges facing its own economy. The sharp decline in FDI and aid since 2018 highlights the limits of China’s ability to sustain massive foreign investments while grappling with its own internal economic problems.

For African nations, China’s pullback represents both a challenge and an opportunity. On the one hand, the loss of Chinese financing has left many countries scrambling to complete infrastructure projects and service mounting debts. On the other hand, China’s retreat has created space for new partnerships, forcing African nations to diversify their sources of finance and adopt more sustainable development strategies.

Ultimately, the decline of China’s financial influence in Africa is not the end of China-Africa relations, but rather a shift in their nature. While China may no longer be the dominant economic force it once was, its strategic interests in Africa remain intact. The future of China’s engagement with Africa will likely be more selective, more strategic, and more focused on areas that align with China’s evolving global ambitions.

In the end, China’s retreat from Africa is a lesson in the dangers of overreach. Even the most ambitious global projects, when not grounded in economic sustainability, eventually face the cold, hard realities of financial limits. And while China’s influence in Africa may be diminished, the story of its engagement with the continent is far from over.

References:

Atitianti, P. A., & Asiamah, S. K. (2023). Chinese foreign direct investment and business start-ups in Africa. African Journal of Science, Technology, Innovation and Development. https://doi.org/10.1080/20421338.2023.2176612

Cudjoe, D., He, Y., & Hu, H. (2021). The impact of China’s trade, aid and FDI on African economies. International Journal of Emerging Markets. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOEM-10-2020-1180

Damiyano, D., Mpofu, M., & Mago, S. (2023). Chinese’s messiah or monster activities on economic growth in Southern Africa? Russian Journal of Agricultural and Socio-Economic Sciences. https://doi.org/10.18551/rjoas.2023-06.01

Donou-Adonsou, F., & Lim, S. (2018). On the importance of Chinese investment in Africa. Review of Development Finance. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rdf.2018.05.003

Fu, Y. (2021). The Quiet China-Africa Revolution: Chinese Investment. The Diplomat. https://thediplomat.com/2021/11/the-quiet-china-africa-revolution-chinese-investment/

Guillon, M., & Mathonnat, J. (2020). What can we learn on Chinese aid allocation motivations from available data? China Economic Review. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2019.01.004

Miao, M., Lang, Q., Borojo, D. G., & Zhang, X. (2020). The impacts of Chinese FDI and China-Africa trade on economic growth of African countries. Economies. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies8030053

Morgan, P., & Zheng, Y. (2018). Tracing the legacy: China’s historical aid and contemporary investment in Africa. International Finance eJournal. https://doi.org/10.1093/isq/sqz021

Ngundu, M., & Matemane, R. (2023). Forecasting China-Africa economic integration using Wavelet-ARIMA hybrid approach. Journal of Infrastructure, Policy and Development. https://doi.org/10.24294/jipd.v7i3.2647

Oladipupo, S., & Ajide, F. (2023). Environmental effect of Chinese FDI in Africa: Evidence from pooled mean group. Sustainable Development. https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.2868

Tasinda, O. T., Ze, T., & Imanche, S. A. (2021). A panel data analysis of the impact of Chinese FDI, remittances, and foreign aid on human capital growth in Africa. Journal of Data Analysis and Information Processing. https://doi.org/10.4236/jdaip.2021.93012

Wang, K. (2023). Impact of Chinese FDI Stock on Urban Development of South African Cities. Highlights in Business, Economics and Management. https://doi.org/10.54097/hbem.v5i.5006

Related Publications

-

China as a Black Sea Actor: An Alternate Route

China’s international role has expanded rapidly in the last decades, and the Greater Central Asian region, Europe, and the Middle East, to which the Black Sea region (BSR) connects, are […]

-

Hegemony at a Crossroads: The Inverse Dynamics of China’s Global Strategy

Here is my bold statement. Hard power projection decimates soft power but only for authoritarian states. In the early 21st century, I was living in Beijing and at that time […]

-

Russia-DPRK Space Cooperation: It’s Politics, Not Science

The recent Vostochny summit between North Korean leader Kim Jong Un and Russian President Vladimir Putin has attracted much international attention. The fact that both leaders pledged to strengthen bilateral […]

-

Unpacking Beijing’s Narrative on Taiwan

Executive Summary Shaping economic rules, technology standards, and political institutions have been the core pillars of Chinese leader Xi Jinping’s efforts to advance his authoritarian model and weaken democratic processes […]

-

The Economic Leash: China’s Financial Tethers and Global Power Plays

China’s emphasis on Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth and its integration into global markets have allowed it to wield significant influence internationally. Nonetheless, this focus on rapid expansion has created […]