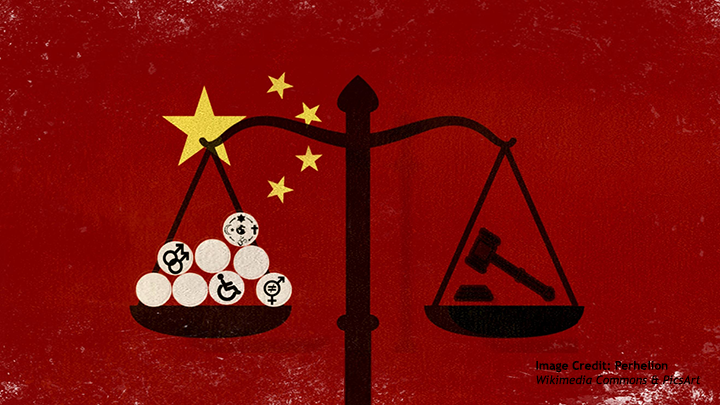

Taking Stock of China’s Anti-Discrimination Legislation

ISDP

Summary

- China’s transition to a socialist market economy in 1978 – resulting in increased competition, especially in the labor market – introduced greater opportunities for discrimination.

- Since the 1990’s, China has enacted laws and regulations aiming at promoting equality in such fields as employment and health, but also providing greater protection against discrimination towards certain groups.

- However, relevant laws and regulations relating to discrimination remain scattered throughout different pieces of legislation. The absence of a comprehensive anti-discrimination law coupled with a lack of sufficient enforcement mechanisms for the regulations in place means the fight against prejudice remains somewhat unqualified.

Introduction

Since the end of the 1970s, China has experienced a surge in legal acts, as part of a legalization policy aimed at strengthening its legal system and building a modern society. In this vein, codification of its first civil code, which will become effective in 2021, has taken the Chinese legal system a step further in protecting the rights of individuals in various areas such as marriage and property. While equality before the law is reiterated, the absence of the principle of non-discrimination seems rather paradoxical, especially in a context of international pressure on China to address inequalities and discrimination domestically. Yet, China’s legislation has not been completely silent on the issue.

Equality has been a central principle since the establishment of the People’s Republic of China. It has featured in all versions of the Chinese Constitution and the state-planned economy guaranteed unprecedented access to employment, education and health services, though the offset of this has been an extremely controlling and repressive regime.

In 1978, economic reforms generated considerable growth and alleviated hundreds of millions of people out of poverty. However, as the transition to a socialist market economy introduced competition, especially on the labor market, opportunities for discrimination also increased. In a context of labor oversupply, recruiters in both the public and the recently formed private sectors have explicitly barred certain groups such as women or migrant workers from hiring processes, especially for high-paying positions. Although the new Constitution in 1982 had reiterated the principle of equality, lawmakers came to the realization that China’s legal and institutional apparatus was not prepared to handle such practical social consequences.

In an attempt to rectify the situation, China has enacted a handful of laws and regulations aimed at preventing discrimination since the 1990s. This backgrounder takes stock of China’s anti-discrimination legislation and attempts to answer the following questions: What constitutes China’s anti-discrimination regime? Has it been effective in fighting discrimination? What are its main legal shortcomings? What social and political challenges lie ahead of a more egalitarian and inclusive society?

Initiating an Anti-Discrimination Regime in China

Various sources form China’s anti-discrimination legislation. The 1982 Constitution has enshrined the principle of equality of all citizens before the law (Article 33). Articles 4, 36, 48, and 89 also guarantee the rights of ethnic minorities, religious freedom and gender equality and prohibits discrimination on those grounds.

This principle has been complemented with further pieces of legislation. While there exists no comprehensive non-discrimination law in China, the issue has been addressed by specific laws and State Council regulations concerning various policy fields or disadvantaged groups.

The most developed area is employment law, where prohibition of discrimination is explicit and legal remedies and penalties are provided.

The Labor Law (1994), which was adopted to respond to the recent economic and social changes, forbids discrimination on the basis of race, ethnicity, religious belief and gender. It refers to the observation of special rules for persons with disabilities and ethnic minorities and provides further rights for women such as maternity leave, though it also prevents them from engaging in labor-intensive work.

The Employment Promotion Law (2007) extends the coverage of protected groups to include migrant workers and carriers of infectious diseases, although some restrictions are also stated for the latter. Moreover, the law provides for workers with the right to engage legal proceedings for employment discrimination before the People’s Court and workers whose rights have been infringed are eligible for compensation.

The Employment Service and Employment Management Regulations (2008) was issued by the Ministry of Labor and Social Security to complement the newly enacted Employment Promotion Law. It gives more precision s concerning forbidden practices such as conditioning women’s employment to their marital status and to their pledge to not have children within a certain period or using a hepatitis B status to screen candidates. It also introduces a 1,000 RMB fine for companies and organizations that are found in violation of the law.

Non-discrimination provisions can be found in other areas such as the Compulsory Education Law (2006) and the Advertising Law (1994). Article 29 of the Compulsory Education Law contends that teachers should not discriminate among their students. And Article 19 encourages the integration of persons living with disabilities in the general school system. Article 7 of the Advertising Law provides that “an advertisement should not feature contents that are discriminative against nationalities, races, religions and sex;” and Article 8 specifies that “advertisements should not feature content that is injurious to the physical and mental health of persons living with disabilities”. However, relevant laws and regulations have yet to define the behaviors or content that can be discriminatory.

In addition, numerous laws and regulations have provided varying degrees of protection against discrimination towards certain groups, namely women, persons with disabilities, migrant workers and persons living with infectious diseases. The next section provides an overview of the legislation for each group. Though Chinese law does not foresee their protection, the situation of sexual and gender minorities has made a few breakthroughs that will therefore be discussed. Finally, the developments experienced by ethnic minorities, which have received much attention, will be addressed in this paper.

Breaking Down the Main Prohibited Grounds of Discrimination

Groups that Receive a Certain Level of Protection (Albeit Imperfect)

Gender-Based Discrimination

The Law on the Protection of Rights and Interests of Women (1992) is the main piece of legislation that guarantees women’s equal rights with men in the political, cultural, educational, employment, property, individual and family spheres. More particularly, many discriminatory practices are explicitly prohibited, including raising school enrolment or employment standards for women, refusing to hire women or forcing them to sign work contracts that restrict their right to marry and to bear children, as well as discriminating against women in their equal access to promotion, benefits, property and succession. The law also outlaws abandonment and infanticide against female children, and sex selective abortion is banned under:

The Law on Maternal and Infant Health Care (1994) and the Law on Population and Family Planning (2001). Moreover, the 1992 law provides for legal remedies in case of violation of those rights, with women’s organizations playing a central role in providing legal aid. The law was amended in 2005 when it introduced the prohibition of sexual harassment for the first time. Nonetheless, women have continuously been excluded by law from engaging in physically demanding jobs such as mining.

Despite existing legislation to redress inequalities, gender-based discrimination remains commonplace as these laws are hardly enforced. Indeed, discrimination starts early on as numerous cases of selective abortions and abandonment of female children are still ongoing in a country that used to apply a one-child policy and traditionally values sons over daughters. When applying for higher education, universities often require women to score better than men at the entrance examination and many still apply gender ratios favoring men.

The economic reforms have also had a lasting negative impact on gender equality in recruitment processes. With an increased competition on the labor market, women are subject to discriminatory practices such as conditioning their employment to marriage and maternity factors. Female employees are also paid 17 percent less than their male colleagues and only 21 percent of the top manager positions in Chinese companies in 2018 were occupied by women. With such unfavorable conditions, women often go through longer periods of unemployment.

Many have brought cases to the People’s Court. For example, in 2013, a young Beijing graduate filed a suit against Juren Academy for advertising a “men only” administrative assistant position with the help of Yirenping, a non-governmental organization (NGO) that provides legal assistance in discrimination cases. The plaintiff settled for 30,000 RMB and a formal apology in what is believed to be the first gender-based discrimination lawsuit in China. Nonetheless, offers advertising “‘men only” or “married [women] with children” jobs have remained commonplace, including in the public sector, and the situation is unlikely to change despite the recent Circular about Further Regulating Recruitment and Promoting Women’s Employment (2019) which reiterates the prohibition of using marriage and maternity as conditions for employment and imposes a 50,000 RMB fine on recruiters that resort to gender-discriminatory job advertisements.

Discrimination Against Persons with Disabilities

Persons with disabilities are protected in all aspects of political, economic, cultural, social, and family life under:

The Law on the Protection of Persons with Disabilities (1990). The law explicitly prohibits discrimination on the ground of disability and provides plaintiffs with legal remedies. Compulsory and incentive measures are also specified in the Regulation of Employment for People with Disabilities (2007) such as a 1.5 percent target of persons with disability within an organization’s employee base, payment into the employment security fund for persons with disabilities if the target is not met as well as the extension of the tax reduction and exemption scheme for those that reach the quota. The Regulation on the Education of Persons with Disabilities (1994, amended in 2017) attempts to promote the concept of integrated education by requiring regular schools to accept children with disabilities who can adapt to learning in general education in a classroom environment. Those schools which turn them away are subject to administrative penalties.

Some lawsuits resulted in the improvement of service accessibility for persons with disabilities. For example, in 2012, Mr. Xuan Hai, who is visually impaired, filed a lawsuit against the Anhui provincial government for failing to provide proper arrangements for candidates with disabilities willing to take the civil service examination. Although he lost the suit, his demands have been heard as the local government now provides electronic versions of the examination and accessible software for visually impaired candidates.

However, persons with disabilities still have limited education and employment prospects. When they are not rejected, children with disabilities are not given appropriate support. Many companies prefer to pay a penalty rather than striving to reach the 1.5 percent target. As a result, disabled workers are often relegated to low-paying roles such as massaging or piano tuning by default. Expressing criticism is often risky as it can likely cause the loss of one’s benefits.

Discrimination on the Ground of Household Registration Status

The end of collective farming and the implementation of the economic reforms in the 1980s saw waves of migrations, particularly from rural to urban areas, to supply the need for labor force in developing Chinese cities. Internal migration has continued over the years and in 2019, the number of rural migrant workers in China was estimated to be 291 million. However, the rules of household registration (hukou) have not been dismantled and they continue to form the basis for discriminatory and marginalizing practices by local governments against migrant workers, which include forbidding them to apply for and perform certain (high-paying) categories of jobs, excluding them from public housing schemes or refusing public school spots for migrant workers’ children.

In 2003 and 2006, the State Council issued directives urging local governments to remove discriminatory policies towards migrant workers. The Employment Promotion Law (2008) should guarantee them equal pay and equal job opportunities with urban locals. Moreover, the Labor Contract Law (2008) was enacted to provide more security regarding the terms of their contracts.

Apart from wages, unequal benefits are another problem. For example, while some local governments such as Shenzhen and Hangzhou provide the same level of insurance for both migrant workers’ and urban locals’ children, restrictions remain commonplace. Some legal aid stations such as Zhicheng gongyi have taken on the task to defend migrant workers’ rights in mediations and trials.

Discrimination Against Persons Living with Hepatitis B and AIDS

In China, where there are an estimated 120 million people living with HBV40 and 968,000 people living with HIV, there exists a widely believed misconception that hepatitis B and AIDS can be spread through casual contacts. People living with either disease are largely denied employment and education opportunities after going through required health examinations.

Changes started to occur when several lawsuits arguing discrimination against people living with hepatitis B were brought to the People’s Court. In 2004, a court in Wuhu (Anhui province) ruled in favor of Zhang Xianzhu who sued the local government for denying him the opportunity to become a civil servant after his health examination revealed he was a hepatitis B carrier despite provincial health standards allowing him such opportunity. In 2013, a man who was denied a teaching job in Jiangxi province became the first person to receive a compensation for discrimination because of his HIV/AIDS status.

Apart from the introduction of infectious disease status as a prohibited ground of discrimination by the Employment Promotion Law (2007), advocacy by NGOs such as Yirenping led to the introduction of the Notice on Cancellation of Hepatitis B Test Items in School Admission and Employment Examination (2010) which further regulates and controls the use of health examinations. Nonetheless, cases of HBV carriers being screened in recruitment processes and HIV patients being denied treatment in hospitals remain commonplace.

Non-Protected and Persecuted Groups

Discrimination on the Basis of Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity

In China, homosexuality was decriminalized in 1997 and removed from the Chinese Classification of Mental Disorders in 2001. Trans identities still feature in the Classification. Although public acceptance of sexual minorities and exposure to LGBT+ related content have improved, there is to date no law or regulation that protects the rights and interests of LGBT+ persons. This legal void leaves them extremely vulnerable to discrimination and makes it hard for them to seek justice. In 2014, a Shenzhen court ruled against a man who was dismissed after the release of a video in which he was outed as a homosexual. In a positive development, in 2016, a healthcare worker received a compensation after he was sacked because of his transgender status, though the court did not recognize discrimination based on gender identity.

Discrimination on the Basis of Ethnicity

The Chinese government recognizes the existence of 56 ethnic groups (minzu). The country is populated by a majority of Han Chinese, with the remaining 55 minority nationalities or ethnic minorities (shaoshu minzu) accounting for over 8.5 percent of the whole population. Part of them live in autonomous regions – Guangxi, Inner Mongolia, Ningxia, Tibet and Xinjiang – which were slowly introduced in the 1950s-60s and tensions with the central government have been recurrent.

The Law on Regional National Autonomy (1984) regulates the relations between the central government and those autonomous regions where a greater proportion of ethnic minorities are settled. It claims their freedom to retain their own culture and to enact specific regulations, though such decisions are subject to approval by the central government under the principle of “democratic centralism”. Bilingual education should be allowed, and translation provided in legal proceedings. In an attempt to foster integration, the Communist Party of China (CPC) put in place affirmative actions in favor of ethnic minorities, including tax benefits and quotas at university entrance and for civil servant positions, on top of investing in economic development and infrastructure modernization in autonomous regions. However, such measures gave rise to resentment from Han Chinese and many local governments have already started to roll them back.

Furthermore, tensions between ethnic minorities and Han Chinese have continually increased over the years as assimilation is being forced on ethnic minorities. Indeed, restrictive measures imposed in autonomous regions such as pressuring local schools in Tibet to increase the use of Mandarin Chinese in education at the expense of Tibetan language, serve the purpose of advancing “ethnic unity”.

In recent years, control of ethnic minorities has become even more egregious, especially for Tibetans and Uyghurs among whom independence sentiment is more prevalent. National unity, that autonomous regional authorities shall uphold under Article 5 of the Law on Regional National Autonomy, is a matter of national security under the National Security Law of the People’s Republic of China (2015). Arrests are often justified by national security concerns under the accusation of inciting separatism, rebellion, and state subversion. Repression culminated in 2018, when the discovery of internment camps in Xinjiang, where an estimated one million Uyghurs are being detained, has sparked international public outcry. In this context, bringing a suit to denounce discrimination based on ethnicity is nearly impossible as those who claim their rights under the law might end up being charged for “inciting separatism”.

Main Legal Obstacles of the Current Regime

As seen in the previous sections, anti-discrimination laws and regulations have not been seldom, and anti-discrimination movements scored several victories in landmark suits. Indeed, some courts ruled in favor of the plaintiff in hepatitis B-based employment discrimination cases before infectious disease status officially became a prohibited ground of employment discrimination.

However, though the issue has received attention in laws, regulations and court cases, China does not have a comprehensive anti-discrimination law with a legal definition of the term. As a result, it might be difficult to determine what constitutes as discrimination and develop a systematic approach to discriminatory behaviors or practices in all policy areas. The fact that China’s anti-discrimination legislation is scattered in different laws and regulations which foresee different legal proceedings adds to the confusion.

Moreover, China’s anti-discrimination laws have been criticized for their lack of enforcement mechanisms. As seen in the aforementioned cases, many discriminatory practices that are supposed to be prohibited by national and local laws and regulations such as screening candidates living with hepatitis B or AIDS are still ongoing. In a society where trials are the least preferred mechanism to settle a dispute, those who make the decision to sue also have to go through a tedious process before their case might be accepted by a court.

Finally, remaining “protective” provisions are likely to accentuate discrimination. For example, women have continuously been prevented from engaging in labor-intensive work such as mining or scaffolding as such jobs are “unsuitable” for them. The existence of such provisions reinforces already deep-rooted stereotypes about women’s capabilities as will be shown in the next section. Some analysts suggest that the legislation should seek to empower women by admitting them in such professions while keeping them aware of the risks, rather than simply deciding for them.

Social and Political Challenges Ahead

In addition to legal obstacles, various social and political factors are likely to stall anti-discrimination efforts. Entrenched stereotypes can hinder the move towards non-discrimination and greater inclusivity. In the case of gender discrimination, having a son is traditionally more valued in Chinese society as he enables the perpetuation of the family lineage. In such view, men are responsible for important family decisions and fully enjoy the right to inheritance, while the women’s responsibilities are limited to housework and bearing children. Though more women have had access to higher education over the years, they often remain excluded from high-paying positions as it is widely believed that women will dedicate themselves to their family once they marry while men need greater responsibilities to support their family financially.

Moreover, studies by Lu Jiefeng (2015) and Lin Zhongxian & Yang Liu (2018) on discrimination against migrant workers and persons with disabilities have shown that in the process of acknowledging a situation where they have suffered a grievance, many respondents tend to blame themselves for being weak rather than the others for violating their equal rights. Indeed, in a society which cares about saving face, it is not uncommon to interpret discrimination as a sign of one’s own weakness – being from a low social class for migrant workers or not being physically or emotionally strong enough to be independent and gain people’s respect for persons living with disabilities.

Some activist groups such as Yirenping have taken on the mission to defend disadvantaged groups and have successfully brought discrimination lawsuits to the People’s Court. However, as the Chinese government is tightening its control on society and cracking down on dissent, such organizations are starting to be viewed as a threat to “social harmony”. In March 2015, the Beijing Yirenping Centre was raided down and one employee was detained after the group campaigned for the release of feminist activists arrested ahead of International Women’s Day. The Law on the Administration of Activities of Overseas Non-Governmental Organizations within the Territory of China (2017) has imposed further registration requirements and supervision upon international and domestic activist groups.

A question often raised by journalists and policy analysts is, how does China justify such choices under its commitments at the international level? Indeed, it is worth reminding that the right to non-discrimination is an integral part of the United Nations Human Rights regime. The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights – that China has yet to ratify – states that “the law shall prohibit any discrimination and guarantee […] protection against discrimination on any ground such as race, color, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status.”

In addition, China is party to the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination and the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, which are all monitored by the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. China does not reject its participation to the international human rights regime but has always offered a different interpretation of human rights that emphasizes collective rights such as the right to economic and social development over individual rights (see backgrounder on human rights in China). Such an approach is also reflected in its domestic anti-discrimination legislation which is expected to continue insisting on employment, education, and health issues rather than on increasing representation and advocacy in the public sphere.

In recent years, the growing use of new technology is encroaching on issues of data protection and privacy, as well as to anti-discrimination efforts. For instance, while the launch of a nationwide social credit system is expected for this year, many pilot projects run by local authorities or private companies have already been put in place and started to score their users based on the number of good and bad deeds they are doing. Aimed at improving governance and trust among the society, this scoring system can determine a person’s access to certain services, from buying train tickets to being admitted into the best schools, thereby introducing a new type of discrimination. Moreover, the development of racial recognition algorithms for surveillance purposes by technology companies will inevitably play a role in the discrimination and repression already suffered by ethnic minorities. From this perspective, the prospect for a more inclusive and egalitarian society in China seems rather uncertain.