The Beijing Olympics: Engaging China while Feeling out for Stones

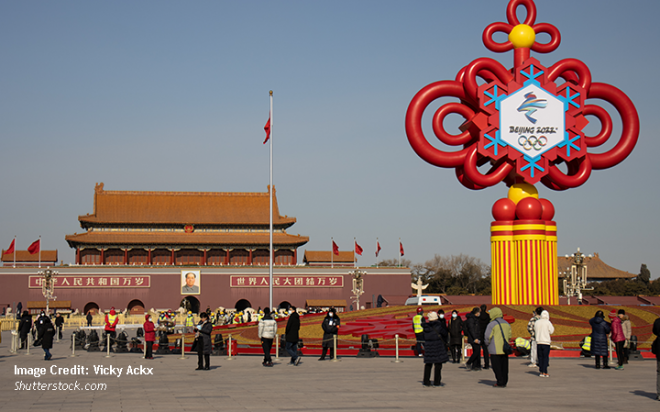

The 2022 Beijing Winter Olympic Games have now opened, fourteen years after China arranged the Olympic Games for the first time in the summer of 2008. On both occasions the games have been fraught with controversy, although the Olympic spirit stands for promoting such lofty values as solidarity and mutual understanding.

The decision to let the authoritarian Chinese state arrange the Summer Olympics in 2008 was the subject of much criticism in Sweden and elsewhere. Critics warned that autocratic Beijing would use the games for its propaganda. The decision to award the Winter Games to Beijing has been even more severely criticized. More frequently than in 2008 these games have been likened to the Summer Games held in Berlin in 1936. Several governments in the democratic world boycotted the opening ceremony by not sending their leaders to attend. It is worth remembering that when the decision about where to hold the 2022 Olympics was finally taken, China’s only competitor was Kazakhstan, another authoritarian state. This should be a source of embarrassment to the democratic world.

The 2008 Precedent

It is not surprising that the criticism of the 2022 games is more severe than in 2008. The PRC government was authoritarian and oppressive then too, but at that time one could still argue that, despite many setbacks, the process of reform and opening up was still going on and China was gravitating away from the Maoist totalitarianism. The core tenets of Deng Xiaoping’s vision were still alive both in actual policies and as inspiration for reform-minded politicians, who sometimes projected more of openness into Deng’s ideas than he may have intended.

These tenets included ideas that China should be ruled by a collective leadership operating under rules that defined the duties and tenures of individuals, that there should be a clear separation of the roles of the Party and the government, that the judiciary should become more independent, and that diversity in culture and education should be encouraged. It was also still common to hear people in the government apparatus say that it had taken a long time to build a democratic system in Western countries and that China needed time as well. It was then very rare to meet people who outright rejected democratic ideals as generally understood in the west, or even go so far as to say that the Chinese system was more advanced or even more democratic.

It seemed that the outside world could engage with China constructively and expand relations in tourism, culture, science, and education etc., since this would be mutually beneficial. In this perspective, holding the Summer Olympics in Beijing seemed to very appropriate. The government in Beijing would no doubt use the games for its propaganda about how good the Party was for China, but more importantly they would stimulate exchange and promote continuing opening up.

Totalitarian Turn

Today, the situation is different. It is true that authoritarian elements, such as one-party rule and disregard for basic human rights have been salient features of the PRC since 1949. But now the government seems to be rapidly steering China towards even tighter control. Already at the time of the Summer Olympics in 2008 there were signs that the trend towards increasing openness was coming to a halt, a temporary halt many thought, as from the late 1970s onwards the modernization program had been characterized by periodic episodes of tightening and loosening state control. It seemed logical that soon a new period of relaxation and accelerated reforms would set in.

Xi Jinping’s rise to power did not initially dampen these hopes. On the contrary, observers like myself believed that he would be a cautious reformer seeking to overcome contradictions and reach compromises. Well placed friends in China were convinced that he would use the first year or two in office to consolidate power and then return to the road of continued reform. But this did not happen. On the contrary it has become clear that Xi is steering China back towards a more totalitarian rule. He has managed to have the formal limits on his time in office removed and is now recognized not only as the paramount political leader but also as the foremost ideological and spiritual authority. In this regard he has become a new Mao.

Domestically oppression has increased and the violations of human rights become more serious. In Xinjiang internment camps have been set up for more than a million Uyghurs and other members of Muslim minorities, euphemistically referred to as “vocational education and training centers”, as part of “a people’s war on terror”. Many governments and human rights organizations have condemned these for serious violations of human rights and even described them as part of an ongoing “cultural genocide” or just a “genocide”. The clampdown on the democracy movement in Hong Kong is another example of modern China regressing towards totalitarianism.

Xi’s autocratic turn, has also manifested itself internationally. Deng Xiaoping’s principle to “hide your strength and bide your time” has been relegated to the past. Instead, wolf warrior diplomacy and threats have come to characterize the PRC’s international behavior. Xi now speaks about “reunification” of Taiwan with Mainland China in terms that cannot but be seen as threatening to Taiwan’s democratic order and to peace.

All this does not mean that everything Xi and his government do should be condemned outright. The policies launched to shrink the economic gaps in Chinese society and achieve “common prosperity” define goals that are decisive for sound and sustainable development. Hopefully some of these policies will also lead both to a more just distribution of wealth and to improvement in the livelihood of many people. But one must also recognize that the efforts to tighten control over successful companies set up by new entrepreneurs, who have played a crucial role for achieving the successes of the modernization program, also aim at protecting Xi Jinping’s position and the Party’s control.

It would also be a mistake to conclude that efforts to curtail corruption are wrong, as graft is a serious problem for China. However, Xi’s approach to rooting out corruption has become immensely politicized and again serves to subordinate policy to the immediate interests of the paramount leader.

Engagement

For a short time the media focus will be on the Winter Olympics in China, on the competing athletes and teams, but also on the political implications of the games. Hopefully, the discussions that this generates will lead to a deepened understanding of today’s China and of international politics. This is a good opportunity to review the changes that China has undergone in the period between the Summer Olympics of 2008 and the Winter Olympics this year. It cannot have escaped the reader that in my perspective the results of such a a review are not encouraging. In the words of the political commentator Fareed Zakaria “under President Xi Jinping, China has since turned aggressive abroad and repressive at home”. This retrogression in China has taken place in an international context characterized by increasing international and ethnic conflicts, the rise of authoritarianism and of democracies in decline.

Against the background of this perception of China and the world, it has become commonplace to hear that the idea to “engage” with China in order to promote peace and progress was naïve and that there is really no alternative to a tougher and confrontational approach to China. In line with this view, many observers and human rights activists have argued that countries like Sweden should have boycotted the Olympic Winter Games.

However, giving up the idea of engagement would be to risk throwing out the baby with the bathwater. A China policy based on confrontation rather than engagement would increase tension and further nurture insular nationalism and xenophobia in China. It would be misleading to see a clear-cut choice between engagement and confrontation. It is true that in the name of engagement Western governments have at times been naïve about the risks of close cooperation with China. The security risks of trade and joint ventures in some fields have been underestimated and so have the risks of dependence on deliveries from China. It is also true that in some cases a firm and uncompromising approach may be unavoidable. For example, how can Sweden be expected just to turn the other cheek to the Chinese leaders, when they threaten to “punish” us for demanding that they release the Swedish citizen Gui Minhai, who was sentenced to ten years in prison in a closed-door trial on unclear charges?

It seems that the key decision cannot simply be either engagement or confrontation but rather how to strike a balance, to seek engagement within limits, forms of engagement that promote mutual understanding but do not encourage threats to our security. Few tasks can be more important today than to grope our way towards such a balance and, in the words of Deng Xiaoping, “to wade across the river by feeling out for stones”.